Humboldt Parkway, once home to vibrant public space, was destroyed by the Kensington Highway, displacing over 600 families and leaving a concrete gash through Buffalo’s network of city parks. With federal support, the Kensington Expressway Project aims to reconnect the community.

Remembering Humboldt Parkway

The city of Buffalo, New York is sometimes referred to as a “city within a park.” Buffalonians are proud of their system of parks and the architect who designed them, Frederick Law Olmsted. Olmsted envisioned a network of tree-lined parkways to connect people to the city’s parks via an “emerald necklace” around the city’s core.

Perhaps the most famous stretch of this “emerald necklace” was the Humboldt Parkway, which connected the Olmsted-designed Delaware Park and Martin Luther King Park via a two-mile long, 200 foot wide parkway with a bridle path for horses down the middle, flanked by rows of maple and elm trees and separated by a 150 foot wide center median.

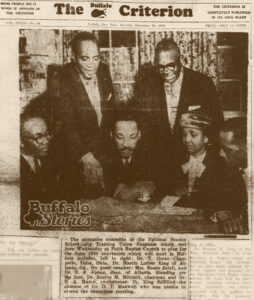

After its construction in 1870, Humboldt Parkway was a thriving public space and quickly became the nucleus of Buffalo’s Black community—a legacy that continues today. (When Dr. Martin Luther King, Jr. visited Buffalo in 1959, he spoke at Faith Baptist Church on Humboldt Parkway.) These communities benefited from the Humboldt Parkway’s beautiful design, building luxury homes and developing a prosperous business community.

But this thriving community would soon be demolished to make way for the automobile.

Enter the Kensington Expressway

After World War II, with white Buffalonians fleeing to the suburbs, Humboldt Parkway became less of an “emerald necklace” and more of a commuter freeway. By 1953, the parkway was carrying over 300,000 cars per day. At the behest of the city’s business community and suburban commuters, city and state officials decided to scrap Olmsted’s plan and bulldoze the Humboldt Parkway in favor of a 6-lane highway, which they would call the Kensington Expressway.

Community members, who were mostly Black, fought tooth and nail against this project, but they were ignored. At a 1954 public meeting of over 200 community members opposing the project, Buffalo officials characterized those in attendance as “an angry minority of homeowners in the Kensington section who were looking to stand in the way of progress.”

So while community members were able to stall the project for 12 years, city and state officials rammed it through. By 1971, over 600 families had been evicted from their homes and all the green space on the Humboldt Parkway was gone. The Kensington Expressway became, and today remains, a major commuter corridor from the suburbs into downtown Buffalo. But the surrounding neighborhoods were never the same.

Fight to restore Humboldt

Despite the removal of the Humboldt Parkway, its memory remained. In fact, many people who lived through the heyday of Humboldt Parkway are still alive today, and you can listen to their fond memories of it here.

Those memories inspired local leaders to form the Restore Our Community Coalition (ROCC), which sought to take action to bring back the people-centered design of the old Humboldt Parkway and reconnect the communities that surrounded it. ROCC was officially incorporated in 2010, but had been working with city and state leaders to recreate the Humboldt Parkway since 1990. By 2012, ROCC and the diverse coalition that formed around them had secured state funding for the New York State Department of Transportation (NYSDOT) to study the design alternatives and economic impact of reconnecting the communities divided by the Kensington Expressway. The ROCC’s idea was gaining traction.

In 2019, NYSDOT announced an official plan: build a “deck” over approximately 4,100 feet of the Kensington Expressway that would cover the highway with an extended Martin Luther King, Jr. Park and a Complete Street reminiscent of the Humboldt Parkway.

Federal support

In February 2023, in a massive show of support for the project, the U.S. Department of Transportation (USDOT) selected the Kensington Expressway “deck” for an award under the new Reconnecting Communities Pilot Program (RCP). The award consists of $55.59 million (30% of all 2023 program funds!), which will be used to fund the implementation and construction of NYSDOT’s 2019 “deck” plan. The RCP was created by the Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act of 2021 (IIJA) to remove or at least mitigate the damage done by highways that divide communities. And because the RCP is still in its pilot phase, this gigantic award to Buffalo will likely set the standard for future applicants.

Empire state of mind (for highway removal)

This award in Buffalo, when combined with Rochester’s Inner Loop removal and the plan to remove I-81 in Syracuse, establishes New York State as a national leader in reconnecting communities projects.

Make no mistake, each of these projects has been driven first and foremost by dogged local advocates working for decades to spur local officials into action. But all the same, NYSDOT has largely been a willing partner. NYSDOT has by no means abandoned the practice of harmful highway expansions, but is taking steps in the right direction.

Lessons learned

What went right in Buffalo? Though Buffalo and NYSDOT are more open to these sorts of projects than are other local and state governments, this project was not guaranteed.

Persistence. It took the ROCC 20 years to even get an official study done of the Kensington Expressway, and another decade to get funding on the table. But throughout that time, they held community meetings, routinely updated their mailing lists, and were vocal in the local media.

Preserving the history. Perhaps most importantly, the ROCC and other advocates in Buffalo harnessed the power of the memories of those who grew up around the former Humboldt Parkway. Through intensely personal stories, the ROCC was able to tie the restoration of the Humboldt Parkway to Buffalonians’ proud identity as a “city within a park”. Who could be against restoring the “emerald necklace”?

Communities around the country should take notice of the ROCC’s strategy that is centered on collective memory. Every American community has members that grew up before the interstate highway boom of the 1960’s. Advocates should gather their stories, documenting what life was like before neighborhoods were divided by asphalt. They should focus on marginalized communities that were most impacted by construction.

On a personal note, part of the reason I got into this work is because of the stories my grandmother told me about her family being displaced from their Bronx apartment due to the construction of I-95 during the late 1940’s.

These stories are powerful! Use them for good, so the next generation can grow up in connected communities like our forebears.

The post Restoring Buffalo’s “Emerald Necklace” appeared first on Transportation For America.