If President Trump is interested in claiming the mantle of “infrastructure president,” here’s a list of specific actions the president can take to make significant improvements to the federal transportation program.

As we’ve done for past presidents, we’ve put together a list of specific actions that President Trump should take on transportation in his final term. Buckle up for this detailed list of 14 specific to-dos across five different areas:

- Finally fix stuff

- Actually improve safety

- Streamline the process

- Reconsider the (broken) models

- Improve transparency

As T4A director Beth Osborne wrote recently, the federal transportation program has been failing to deliver for decades. Spending more money has failed to improve congestion, emissions, efficient access to jobs and daily needs, or reduce the number of people struck and killed while walking. President Trump could make a powerful statement by acknowledging that our current strategy isn’t working and urging Congress to beach this rudderless ship of a program that’s sailing off in no particular direction at all.

1) FINALLY FIX STUFF: President Trump can be the first to finally focus federal spending on fixing things first

He should aim to have “the best” infrastructure rather than just “the most”

Unsurprisingly, the American public doesn’t know much about the federal transportation program.1 Most Americans do not realize there’s no requirement to first repair existing infrastructure before building new assets that require decades upon decades of new, additional maintenance costs. Requiring states to repair things first would likely have immense public support if Congress proposed it, yet a bunch of supposedly fiscally conservative Senators lost their minds at USDOT merely suggesting that states consider doing so.

At some point, we will have to stop expanding a transportation network that is already too large to realistically maintain, or go broke trying. Repair Priorities showed that we’d need $231.4 billion per year just to keep our existing road network in an acceptable state and bring the backlog of roads in poor condition into good repair over a six-year period. Yet across all units of government, in 2015, we spent just $105.4 billion on all highway capital projects. Step one is to stop digging the hole, especially when the gas tax, the primary source of federal funding, has only been covering a fraction of checks that Congress has been writing since as far back as 2008.

President Trump should step in and tell the freeloading members of Congress that the free lunch is over. Tell them their states can’t just expand their transportation system forever with zero thought given to how their children and grandchildren will pay for its upkeep.

(A) Reward areas that are making improvements in the condition of their roadways with competitive grants and limit the grantmaking for those who are not.

More than $200 billion of the $643 billion in the IIJA went to competitive grants, and every administration puts its own stamp on the projects they choose to advance. Add in criteria to reward those who are being the best stewards of the other federal dollars they have received. Those who are begging Congress for more free taxpayer money to expand roads they can’t afford to maintain should not be rewarded with more grant funding to do anything.

(B) Before providing funding for anything new, require transportation agencies to demonstrate they have funding for its maintenance and repair throughout its useful life.

This is another fact that tends to shock people we’ve surveyed: agencies don’t have to prove they can afford to maintain anything they are building. And they can build something new even if it will jeopardize their ability to maintain things they’ve already built. If you or I are buying a house, we have to prove to the bank that we have stable and sufficient income. But when your state DOT takes federal highway formula money and decides to build a new highway with it, they don’t have to prove to anyone that they have enough money to maintain it even for just the next five years, let alone the next 50. It’s time for that to change. USDOT could institute a requirement like this tomorrow with many competitive programs. For formula programs, President Trump can tell Congress to institute this change in the replacement for the IIJA, which is due in September of next year.

(C) When infrastructure fails, whether by natural disasters or otherwise, require that it be updated for current needs.

When floods, fire, extreme heat, or other changes in weather lead to the loss of a road, bridge, transit line, or anything else, transportation agencies should consider whether that asset needs to be replaced, what needs to be done to reduce the chance of a repeat failure, and how the design should be updated to improve priorities like safety and connectivity. Expanding that asset should only be considered if there is a plan to maintain it, as discussed above.

(2) ACTUALLY IMPROVE SAFETY: Stop paying lip service to safety and get the U.S. off the bottom of the rankings

Transportation Secretary Sean Duffy came in with a stated interest in improving safety. It’s sorely needed—the U.S. sits at the bottom of the rankings of the developed world on traffic safety. The numbers are even more dire for people walking. Safety is always described as a top priority, though states face no penalties for injuries or fatalities increasing on their roads. It’s time to put safety above all else, penalize those who use federal dollars to make it worse, and reward those who are moving things in the right direction.

(A) Reward improvements in safety.

Reward the cities, metro areas, and states with roadways that are getting safer with increased access to competitive grants, and limit the grantmaking for the places that are not. Consider serious injuries in addition to deaths, and especially evaluate the numbers for people walking, biking, or getting around outside of vehicles.

(B) Make it clear that cities and states can and should be testing to see what safety improvements work in what conditions, and fund them to do so.

The Secretary should write a memo making it clear that the guidance in the Manual on Uniform Traffic Control Devices (MUTCD) is never an excuse to stand in the way of progress on safety. If provisions in the MUTCD are leading to bad safety outcomes, states, and other agencies should not follow that guidance and submit reports to USDOT about provisions that make safety worse. USDOT should consider updating the guide to better prioritize safety or, even better, pare it back entirely to only cover the design of signs, markings and signals. The MUTCD was never intended to govern street design.

(C) Cap vehicle safety ratings at four stars for any vehicles that impede the driver’s ability to see in front of or around them.

As the vehicle fleet gets bigger, taller, and heavier on average, people in older vehicles, and especially people outside of any vehicle, are more at risk. Collisions that were only injuries 20 years ago are becoming fatalities today. The National Highway Traffic Safety Administration and other relevant USDOT offices should stop dragging their feet and update the New Car Assessment Program (NCAP) and the Federal Motor Vehicle Safety Standards (FMVSS) on crashworthiness and crash avoidance systems to account for people walking and biking. This is something that’s already been proposed by the National Safety Council. (Page 42)

(3) STREAMLINE: Cut red tape and speed up (good) projects

The President and Secretary Duffy are partially right—good projects do take too long. While we’re also glad that terrible, destructive projects also take too long, there’s absolutely some low-hanging fruit when it comes to improving the process by which projects get planned, designed, and built. Here are three:

(1) Streamline the grant application process for all USDOT grants so that rural and lower-capacity agencies can better compete.

While not easy for any unit of government to navigate, smaller and midsized cities face an uphill challenge with the complex process of applying for USDOT competitive grants. USDOT could do two things to improve that process: First, create an online application and a simple plug-and-play benefit-cost analysis (BCA) calculator so that these places don’t have to hire overpriced consultants. Second, reduce the paperwork and speed up the process for signing a grant agreement. What you might not know when you see that list released of RAISE grant winners (or any other grant program) is that it can take months to years to receive any funding because they have to negotiate a grant agreement with USDOT. Speed that up and simplify that process.

(2) Ensure that project streamlining efforts consistently extend to all modes, all regions, and all transportation agencies.

One reason transit projects get built more slowly (and at higher cost) than highway projects is because Federal Highways (FHWA) district offices and Federal Transit (FTA) regional offices interpret many of the same rules differently. For example, FHWA applies streamlining laws and regulations much more liberally than FTA does. Environmental review should be bypassed or abbreviated for more projects that have clear benefits. And the state DOTs demanding streamlining changes from Congress or USDOT, who subject their local governments to arduous requirements when they subgrant money to them, should stop. This process disproportionately harms the smaller and rural areas this administration claims to prioritize because these places don’t have the funding to take over the project or the size and clout to push back.

(3) Remove burdensome federal requirements to bring down costs.

Highway agencies often feel pressure from FHWA under existing design standards and project development protocols to do things that increase costs, like designing roadways with lanes that are unnecessarily wide for streets where lower speeds are the goal or having to do a costly traffic study before making commonsense improvements like new crosswalks or signals. FHWA claims that state and local agencies have flexibility, but their experience counters that claim.

(4) RECONSIDER THE MODELS: Stop wasting money based on bad data and travel models

(A) Take down the Secretary’s value of time memo.

Rescinding this single memo would have a significant impact overnight. USDOT’s enshrined guidance on the “value of time” leads to an enormous waste of federal money, with billions going toward trying to save certain people a few seconds at a time, claiming that those seconds add up to tens of millions of dollars in economic benefit. Rather than explaining further, just watch our video:

We’ve had the technology for years now to measure the actual time of trips instead of assuming that “slightly faster vehicles on road X = a better system.” The time for inaccurate and misleading proxies has long passed. President Trump should direct Secretary Duffy to rescind this memo yesterday.

(B) Review the accuracy of travel demand models.

Traffic models predicted unimaginable congestion without widening The Katy Expressway in Houston. Yet even after widening it to 26 lanes in some places, traffic got worse, failing to deliver on the projections from the flawed traffic models used to justify the billions spent on it. Yet those same models will be used again and again to justify other similar projects. Agencies (or Congress) almost never look back to evaluate if new projects delivered on the promises made or if the new reality comes close to the rosy projections. Like a weather forecast, we’re mostly just concerned about the predictions for tomorrow and rarely go back five years to consider the accuracy of a past forecast. USDOT should start rigorously comparing past projections with actual outcomes, reporting their findings, and updating the models when there are discrepancies.

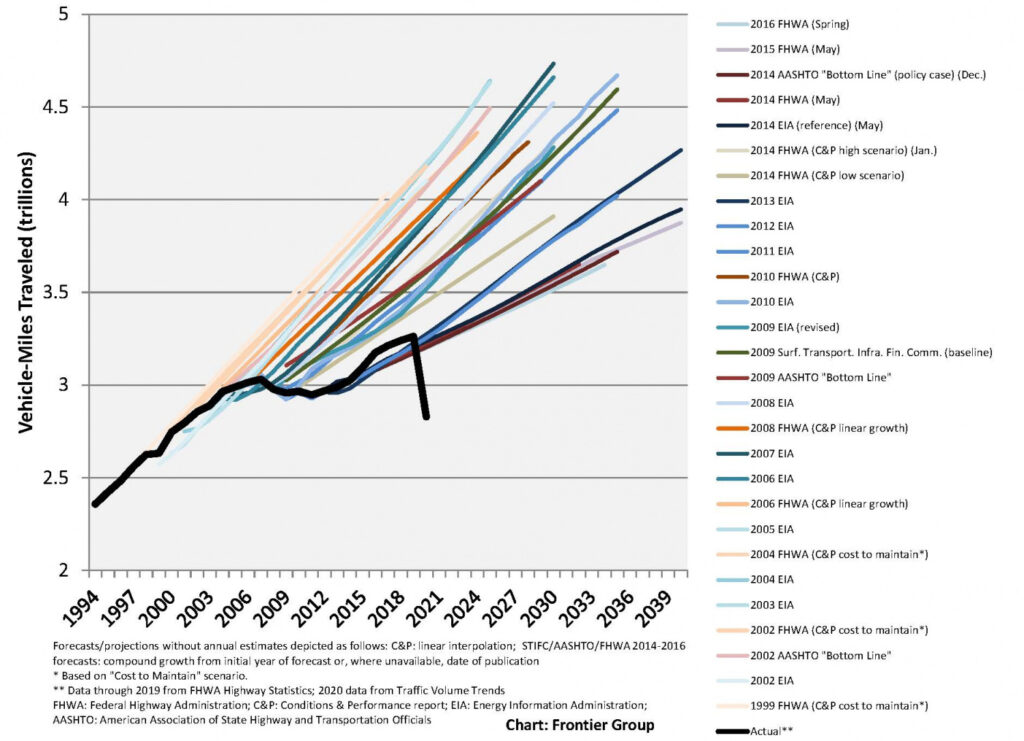

This near-comical graphic from the Frontier Group combines past federal projections of future growth in vehicle miles traveled. The darkest line is reality. Every year the models continued to project basically the same growth in miles traveled, even though every one continued to prove false.

(5) IMPROVE TRANSPARENCY: Make it easier for taxpayers to understand where their money is going and what is being accomplished

The simple truth is that it’s nearly impossible to get up-to-date data on where transportation money has been spent, and the conditions and performance of the transportation system. In fact, when the IIJA expires in September 2026, we’ll just have (an incomplete) picture of where the money went during its predecessor (the FAST Act) from 2015-2021. This means that the members of Congress who will decide how much of your tax money to invest in transportation and how to invest it, have almost no idea about how well the money has been spent for the last 3-4 years. Would you give your employees a raise when you have no idea if they’ve done a good job for the last year? This is yet another reason why public faith in the federal program is incredibly low.

(A) Require project sponsors to report on what their projects have accomplished.

Understanding where and how money is being spent is only part of the question. The administration should also make it easier for taxpayers to learn what has been accomplished with the billions handed out to states and metro areas each year. USDOT should create a new requirement for project sponsors to submit simple reports five years after completion to report on the performance of the project. Did the project deliver all the promised benefits? Did the promised congestion relief materialize? Did the project accomplish its stated goals for improving safety? How does today’s reality match up with the lofty promises used to justify each project?

(B) Standardize transportation spending data format and availability for annual state/metro area spending.

The State Transportation Improvement Program (STIP) is a four-year list of projects a state has committed to funding, planning, and building. Though these STIPS are intended to help the public understand how and where their tax dollars are going and hold leaders accountable, good luck deciphering (or even finding, in some cases) your state’s STIP. USDOT should standardize the format and availability of this data so that the public can easily understand how their tax dollars are spent, compare spending across states and metropolitan planning organizations, and hold their agencies and elected leaders accountable.

(C) Require transparency regarding compensation in leadership positions, including bonuses at Amtrak.

One way to fulfill Amtrak’s mission of reliable, quality passenger rail service is by ensuring that every dollar possible helps them improve or expand service. It’s not unreasonable to provide good compensation to smart, motivated, and competent staff or executives, but salary and bonuses should be tied to serving passengers and justified by quantifiable, measurable results in improved service and travel experience. There should also be accounting for the total number of executive staff, their salaries, and all bonuses.

Stay tuned! We’ll be checking in on these items from time to time throughout this administration and reporting back.

The post What President Trump should tackle on transportation appeared first on Transportation For America.