The technology-driven revolution in urban transport is largely centred on the inner city. It has completely missed the suburbs, which lack the public transport services and shared micromobility devices, such as e-scooters, that inner-city residents enjoy. But new technologies, skilled operators and willing governments may have produced a solution for the suburbs, known as on-demand transit.

Read more:

Billions are pouring into mobility technology – will the transport revolution live up to the hype?

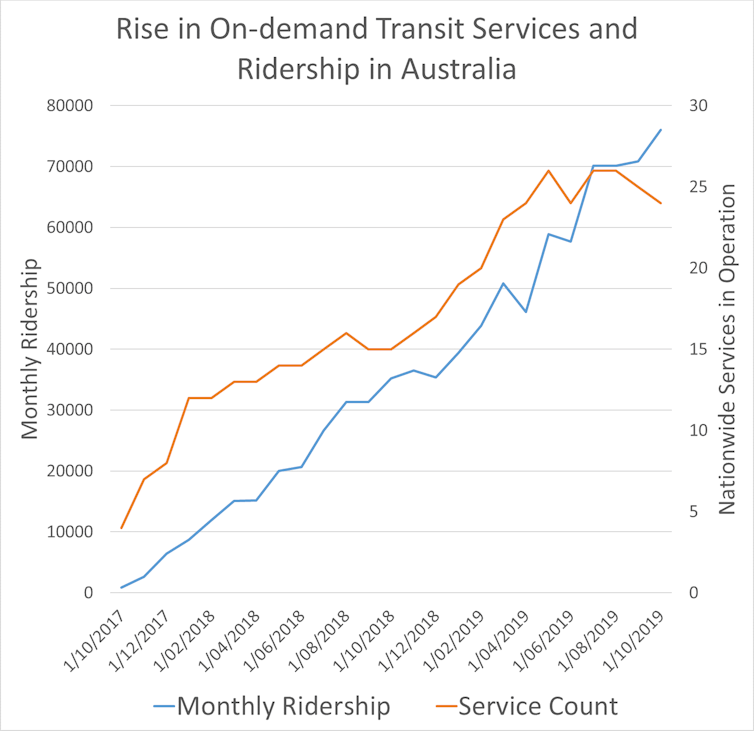

According to our data collection, there have been 36 on-demand trials across Australia since October 2017, providing over 1 million rides to residents. Half of these trips have been in the past six months. Our research at the Griffith Cities Research Institute examines the social equity impacts of these services.

Data provided by the Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads and obtained through Transport for New South Wales open data

What is on-demand transit?

On-demand transit does not follow fixed routes or timetables. Riders book a trip for a cost similar to a bus fare.

Vehicles are often smaller buses, 13-seater vans, or sedans and fleets that can be adjusted based on demand for rides. Unburdened by fixed stops, which are convenient for only a few people, these services can weave their way through communities, optimising routes on the fly.

Simon_sees/Flickr, CC BY

In certain areas of Australia, users simply download an app and request a ride just like a taxi or Uber, but cheaper. Others who would rather not use a smartphone app can book through a call centre or on a computer.

The impact of on-demand services may be much greater than simply adding a local bus route. While billions of dollars go into subsidising inner-city transport, households’ access to jobs and services gets much worse with increasing distance from the centre. Not only do households in the outer suburbs have longer commutes, they also have to drive to get to shops, recreation facilities or health services.

Read more:

Living ‘liveable’: this is what residents have to say about life on the urban fringe

On-demand services allow people who cannot drive or do not have a car to be active members of society.

What is happening now?

Growth in on-demand services and their use has been rapid. Already, it seems some services are becoming too big to fail, as users’ daily reliance on them increases.

The number of operators has grown from seven at the end of 2017 to 22 by December 2019. Monthly ridership has increased nearly 1,000%.

The Northern Beaches service in Sydney, operated by Keolis Downer, has had nearly 27 months of continuous growth. Starting with a measly ridership of 38 passengers, it now carries over 19,000 passengers a month. The service in The Ponds, Sydney, grew from 1,000 to 8,000 riders in its first four months.

In South Australia, home to the most recent rollouts, the Mount Barker service attracted more than 4,000 riders in its first month.

However, not all on-demand services are created equal. Service provision, operations, locations and vehicles vary widely. Some have state-of-the-art technologies and new fleets of specially designed vehicles. Others operate simply under a procurement agreement with the local taxi provider and a call centre.

These trials haven’t been flawless. Eleven trials have closed. Nearly all have revised services, zones, hours or technology. Some services are world-class. Others need further revision.

This state of affairs reflects the speed of development in the field. Operators are learning how to better navigate the suburbs, while governing bodies are refining service requirements.

Read more:

For Mobility as a Service (MaaS) to solve our transport woes, some things need to change

On-demand transit changes lives

The Queensland government and Logan City launched one of the first on-demand transit trials in Australia. Also known as demand-responsive transit, it covers three parts of Logan, south of Brisbane.

Our research surveyed users of this service. Their responses powerfully demonstrate the value of on-demand transport.

Over 50% of respondents either had no driver’s licence or lacked access to a car for regular use. Illustrating the decreased burden on family and increased autonomy the service provides, one respondent said:

I can’t drive, so I depend on my husband to drive me around. With [on demand] service, it gives me freedom.

Commenting on a recent trip, another respondent said they “would have no [other] way of getting there. On-demand transport has been my saving grace.”

Stories like these illustrate the value of on-demand services. For the people who use them, these services are invaluable, improving their quality of life and access to opportunities.

Negative survey responses pointed toward technological hiccups, such as app glitches. Yet, when talking about the service itself, responses have been glowing. Asked what they would change, one person said:

Nothing. It is the best thing since sliced bread.

What’s next?

Expect to see more of these rollouts in coming months. As technology and operations improve, these services are showing public transport in the outer suburbs can no longer be ignored.

If the transition towards mobility as a service (MAAS) occurs as predicted, on-demand transit may play a key role. To develop these services, we need research into fare structures (such as subscriptions), vehicle types and branding, defining operating areas and promoting shared ridership.

The focus of our research will be to develop key metrics to allow for comparison between services, accounting for many of the variables. The private sector holds much of this knowledge, but it needs to become public to help governments plan more and better systems.

![]()

Benjamin Kaufman is a Transport Academic Partnership (TAP) Scholar and receives funding from the Queensland Department of Transport and Main Roads, who have provided some of the data needed for this article. He is also affiliated with the Cities Research Institute at Griffith University and the Griffith School of Environment and Science.