The new infrastructure law authorizes around $650 billion to fund transportation infrastructure through formula and competitive grant programs, some of which have safety as a core emphasis. Here’s what you need to know about the new money and (modest) policy changes to the safety program, as well as how you can make them work for you.

This post is part of a series we are producing at T4America to explain the new $1.2 trillion Infrastructure Investment and Jobs Act (IIJA), which now governs all federal transportation policy and funding through 2026. What do you need to know about the new infrastructure law? We know that federal transportation policy can be intimidating and confusing. Our hub for this law will guide you through it, from the basics all the way to more complex details.

We are facing an astonishing safety crisis on our roads. The first nine months of 2021 were the deadliest first nine months of a year on America’s roads since 2006, with an estimated 31,720 fatalities. There’s no reason to think that 2022 won’t continue this same trend, which prompted Secretary Buttigieg to present a National Roadway Safety Strategy to set a goal of zero deaths and end this crisis.1

One reason we are facing this crisis of preventable deaths is that within most transportation agencies, prioritizing vehicle speed over safety for all users is a deeply embedded priority. Our priority is different, and we need to start there if we’re ever going to make good on USDOT’s new stated goal of zero deaths:

The new infrastructure law does include some bright spots for holding states and localities more responsible for improving safety, which we discuss below. But overall, Congress largely decided to uphold the status quo, failing to reorient the giant formula programs around safety. Now it’s up to USDOT to do all they can to prioritize safety within their program guidance and grant programs, and for applicants to submit projects that improve safety.

Note: this explainer and webinar from America Walks is full of practical advice about “how volunteer advocacy groups, or local governments without a full-time planner” can steer these funds into improving safety.

What’s in the law?

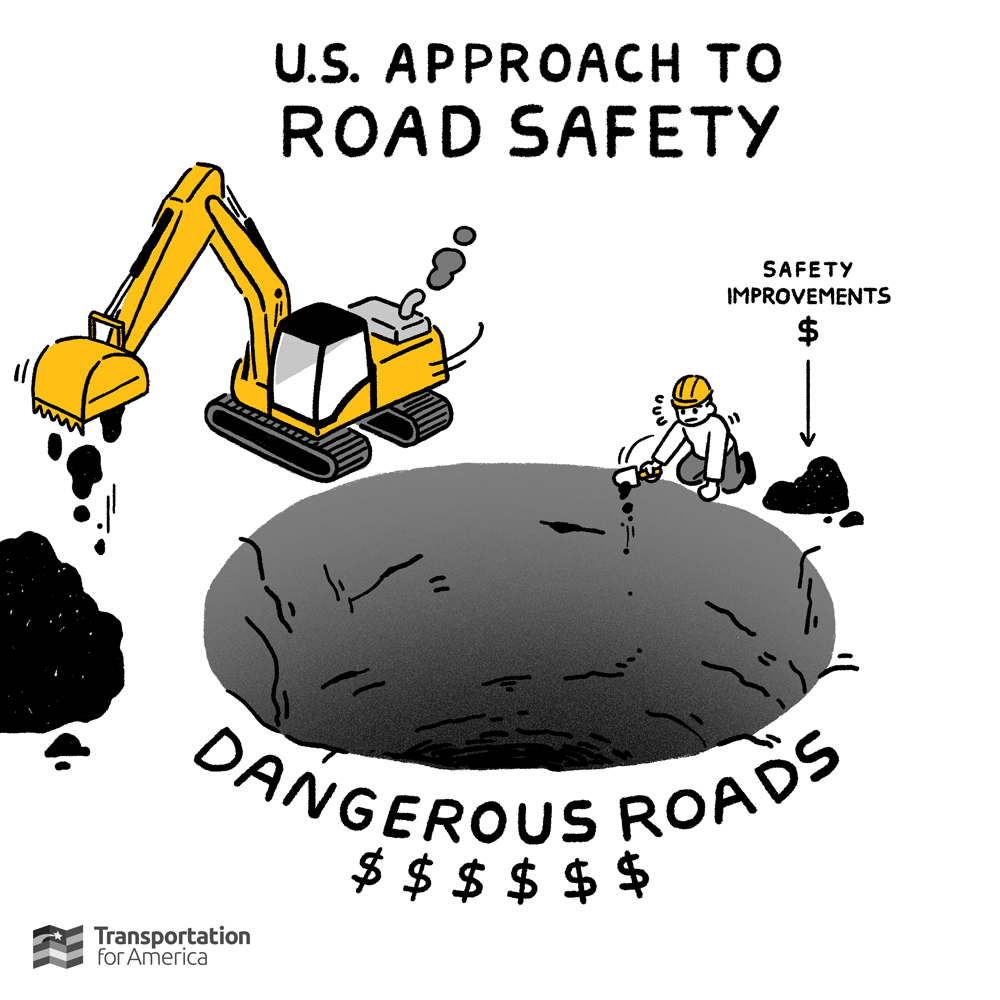

The new infrastructure law does include funding for safety improvement projects like road diets and Complete Streets, but these are spoonfuls compared to the giant excavator of overall road funding where safety is just one of many considerations as we illustrated here:

The new bill does not reorient the transportation program around safety. It allows funding to be used to build safer roads but doesn’t require it. Dedicated safety funding remains a relatively minor amount of the entire program. But the new law does make some alterations to safety policy. One is how we measure state performance and then hold them accountable. If 15 percent or more of a state’s fatal crashes involve vulnerable road users (i.e. pedestrians, cyclists), then a minimum of 15 percent of their Highway Safety Improvement (HSIP) dollars must go toward making those vulnerable users safer.

We’re giving states a small amount of money to improve a problem that transportation agencies can continue to create or exacerbate with a much larger amount of money.

The law also made several other important changes to how USDOT will evaluate safety. It updates standards for the mandatory Highway Safety Plans to change the word for vehicle collisions from “accident” to “crash” (a small but meaningful shift) and to include more public participation and feedback. It updates uniform standards to acknowledge the role of human error in new vehicle technologies. The law allows USDOT to reapportion (i.e., give away) state funding to other states if a state continuously fails to improve their safety outcomes and prevents states from setting worse/lower safety performance targets than the year before. 2

And the law requires USDOT to set minimum performance targets for states in consultation with the Governors Highway Safety Association. This is not an exhaustive list, but overall USDOT does have several more policy levers to create safer roads across the U.S.—if they use their new powers effectively.

Formula safety programs

| Program name | Authorized funding (over five years) | Can be used for: | Should be used to: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation Alternatives Program | $7.2 billion (10% of STBG funding), up from a flat $4.2 billion in the FAST Act, with 41% going to state DOTs and 59% going to MPOs and localities. | Projects that promote modes of transportation other than driving, with notable inclusions being anything eligible under the SRTS program and newly defined “vulnerable road user safety assessments”. | Make roads safer for all users by planning for and building facilities for walking, biking, and other modes that protect those users from high-speed vehicles. |

| Safe Routes to School (SRTS) Program | $1 million minimum to states by formula, based on primary and secondary school enrollment numbers. | Active transportation and complete streets projects, plus education or enforcement activities that allow students to walk and bike to school safely. | Give students safe, convenient routes to school by prioritizing their travel over the speed of cars. |

| Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) | $16.8 billion, apportioned to states by formula. | Highway safety improvement projects, which are defined very broadly, from rumble strips and widened shoulders to data collection and safety planning. | Re-orient highway safety spending toward traffic calming and projects that protect all road users, not just drivers. |

| Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) program | $13.2 billion | Any transportation project that reduces emissions from vehicles, including micromobility (bike or scooter share) and electric vehicles. | Focus emissions mitigation efforts on mode-shift away from driving, not on increasing vehicle speed. Specifically, states and localities should use CMAQ funding for micromobility projects. |

Competitive programs applicable to safety

Some of the safety funding in the infrastructure law is split between several programs, many of which are made available directly to states or localities as competitive grants (more here on best practices for applying to those).

| Program name | Authorized funding (over five years) | Can be used for: | Should be used to: |

|---|---|---|---|

| Transportation Alternatives Program | $7.2 billion (10% of STBG funding), up from a flat $4.2 billion in the FAST Act, with 41% going to state DOTs and 59% going to MPOs and localities. | Projects that promote modes of transportation other than driving, with notable inclusions being anything eligible under the SRTS program and newly defined “vulnerable road user safety assessments”. | Make roads safer for all users by planning for and building facilities for walking, biking, and other modes that protect those users from high-speed vehicles. |

| Safe Routes to School (SRTS) Program | $1 million minimum to states by formula, based on primary and secondary school enrollment numbers. | Active transportation and complete streets projects, plus education or enforcement activities that allow students to walk and bike to school safely. | Give students safe, convenient routes to school by prioritizing their travel over the speed of cars. |

| Highway Safety Improvement Program (HSIP) | $16.8 billion, apportioned to states by formula. | Highway safety improvement projects, which are defined very broadly, from rumble strips and widened shoulders to data collection and safety planning. | Re-orient highway safety spending toward traffic calming and projects that protect all road users, not just drivers. |

| Congestion Mitigation and Air Quality (CMAQ) program | $13.2 billion | Any transportation project that reduces emissions from vehicles, including micromobility (bike or scooter share) and electric vehicles. | Focus emissions mitigation efforts on mode-shift away from driving, not on increasing vehicle speed. Specifically, states and localities should use CMAQ funding for micromobility projects. |

How else could the administration improve the safety program?

In addition to creating robust guidance for administering all of the programs listed above, the Biden administration should modernize the traffic engineer’s go-to guidance (the MUTCD) to reorient it completely around safety and people, and away from its outdated focus on vehicle speed and flow. Unfortunately, the indication from USDOT is that they are punting more substantial edits to a future revision. USDOT closed comments in May 2021 and have suggested that only modest revisions will be forthcoming, but what they choose to change will still matter.3

In addition, the FHWA Administrator’s vulnerable road user research should make sure the agency’s very good recommended safety countermeasures have teeth and recommend substantial design changes, not just behavioral suggestions.

How can the new money advance our goals?

Equity

The safety of all road users is closely tied advancing racial equity and addressing climate change, among many other goals. Our research in Dangerous by Design indicates that low-income and people of color make up a disproportionate amount of the people struck and killed while walking. So providing safe ways for all people to use our streets is critical for advancing our communities’ goals of being more inclusive and connected.

Climate

There is incredible interest and demand in switching more trips from cars to bikes or other modes (an important strategy for cutting down on carbon emissions) but if Americans do not feel safe enough to bike or walk regularly, the ones who have the option to do so will continue to drive.

If you currently don’t bike, what are the main barriers holding you back from doing so? Your answer could be lack of safe infrastructure, perception of safety, ability level, and so on.

— Jerome Alexander Horne (@jahorne) February 15, 2022

Translating federal funding into projects that advance safety is more complicated. As outlined above, formula grants are mostly controlled by state and regional governments who have other top priorities other than safety, no matter how much they profess that safety is #1. Approaching them with projects that have wide and deep support within a community usually gives you the best chance for success. For the highly flexible competitive grants, the America Walks’ explainer contained some concrete advice:

Ken McLeod of the League of American Bicyclists gave a great breakdown of the biggest opportunities in competitive grants for active transportation. First, he said, start by looking at your existing transportation plans. “If you have a plan that is a 20 year plan, and if you are in phase 3, this is like a perfect grant program to get your phase 4 or phase 5 funded in a quicker timeline than you might working through other federally funded programs,” explained Ken.

National Association of City Transportation Officials (NACTO)’s Sindhu Bharadwaj underscored the importance of coalition building for competitive grants. Advocates in small towns or very car-centered regions might be able to acquire some additional funding. The key to their success, though, is focusing and working together. As Sindhu said, funding opportunities can be a chance to bring together a number of organizations and advocates to pick one big goal, like adopting a new design plan. She suggested that the pursuit of funding can be a galvanizing point for a governing body or advocacy group.

So what?

The most important thing to remember is that every single one of the federal transportation programs can be used to improve safety. Safety is always an eligible use. So as you engage with local, metro, and state decisionmakers, you can remind them: If safety is the top priority then every dollar from every program that they have at their disposal can and should go to improve safety for all users. And then hold them accountable: Congress has given them the complete freedom to prioritize safety, so if safety is getting worse, there is no one else to blame.

Considering the crisis of roadway deaths and the limited funding available for safety, it’s critical that we ensure that 1) the safety funding is spent in the best way possible, and 2) that states and metro areas feel the pressure to tangibly improve safety with their bigger, flexible pots of road funding. Creating a vision for what you want to do is a great first step. More from America Walks:

‘I think the most important thing is to have a strong vision locally, and worry about resources next,’ [Beth Osborne of Transportation for America] stated. ‘With good commitment and vision, you can find resources. And…there are tons of places to go for money! You do not have to stay in one tiny pod, you also do not need to make every active transportation effort its own project.’ With that vision, ask your state and local transportation officials how they are planning to seek federal dollars. They ultimately write the grants or propose budgets to elected officials. You need to know if they are working to fund a walkable equitable vision for the community, or are they trying to fund projects envisioned in a prior era. With prompting from community leaders you can help break the inertia of the past.

For planners, engineers, local officials, and other decision-makers, you will be competing with other states, MPOs, and localities for these competitive grants. Understanding the programs in and out will be critical for mustering the financial and vocal support needed to put forth a strong application. That’s how you learn, for instance, that National Infrastructure Project Assistance grants can be used for safety projects.

One last important note we addressed in our competitive grants blog post: Strong local matching funds (ranging from 20 to 50 percent of project cost) are critical to winning these grants, and the process to raise these funds starts by engaging in state and local budget processes far in advance (6-9 months before the start of the fiscal year.) So advocates, this means you should engage agencies early and often on resource prioritization to realize transit projects.

(Note: For the more policy-minded, read our pre-existing funding memos on the programs that the IIJA can fund. Many of them have the possibility to improve safety if used well, but the active transportation memo contains the programs that can be most easily flexed to fund safety projects.)

If you have additional ideas for how to utilize these expanded programs, or have questions about the content listed here, please contact us. Our policy staff is eager to hear from you.

The post The infrastructure law and safety: Will it be able to move the needle? appeared first on Transportation For America.