Gently curving through wetlands southeast of the Great Salt Lake, Utah’s Legacy Parkway has been characterized as an example of a state DOT making a principled compromise to craft a transportation solution balancing transport modes and ecological needs. However, the legacy UDOT had truly left behind was a connection for the new West Davis Corridor, an ongoing project continuing the march through the remaining marshes and farmland of the Salt Lake Valley.

Background

Over the last thirty years, Utah has seen impressive population growth that has been unmatched by most states, but not all responses to growth balance communities’ needs for equity, environmental preservation, and economic sustainability.

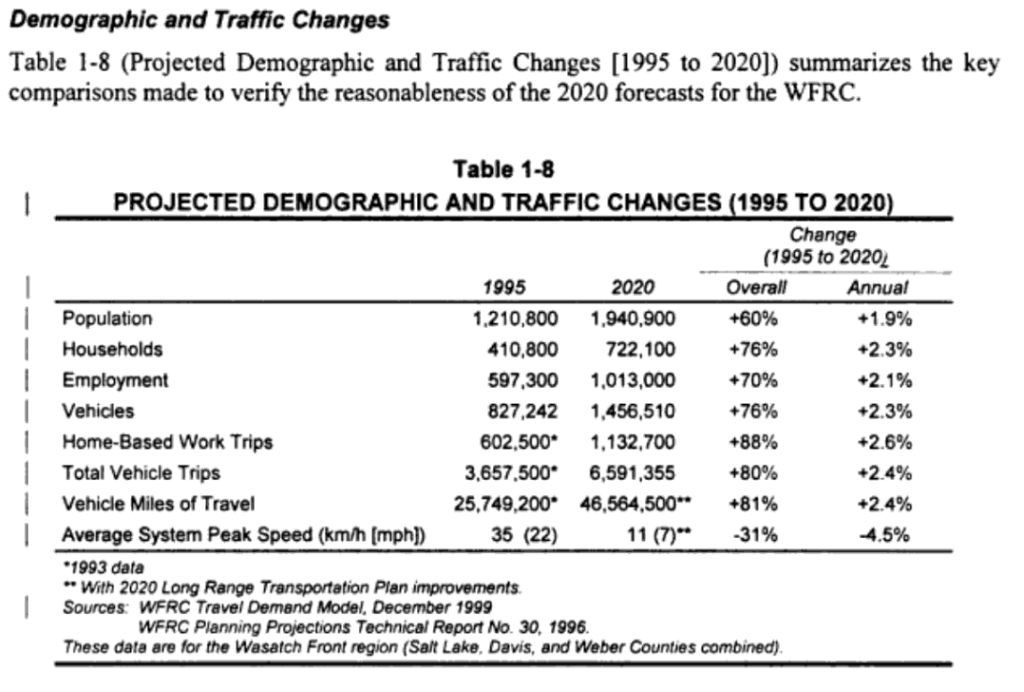

According to projections from transportation planners at UDOT, population and travel demand in the five counties on the east half of the Great Salt Lake were going to increase an astonishing 60 percent and 69 percent, respectively, by 2020. (2020 Census data shows their population estimate was off by about 130,000 people.) Planners warned that at this scale of growth, not building new highway infrastructure would be devastating with travel speeds at peak hours dropping to just seven miles per hour.

To prevent this catastrophe, Utah Governor Michael Leavitt announced long-range plans for Legacy Highway in 1996, a 120-mile highway running parallel to Interstate 15. The first portion of this expansive route would be called Legacy Parkway and double as a “line in the sand” to prevent development west of the highway. Under the Utah DOT’s original preferred plan, that line would cut through 1,568 acres of Utah’s rare wetlands and historic farmsteads.

Advocates push back

Starting in 1997, the Utah Department of Transportation began environmental impact studies for Legacy Parkway as part of the NEPA process, culminating in the release of the Draft Environmental Impact Statement (DEIS) in 1998. In the public meetings following the release, advocacy groups like Utahns for Better Transportation highlighted a multitude of flaws in the study and in the plans themselves. Instead of presenting alternatives to highway routes, UDOT presented the public with alternative highway routes, variations in the right of way that differed only in their relative negative impacts on residences, farms, and wetlands. Residents pointed to the Draft Environmental Statement’s incompleteness and contradictions, finding it had failed to calculate the project’s impact on wildlife, paradoxically associated higher air quality with increasing vehicle travel, and neglected to evaluate transit and land use among the alternatives. In a report commissioned by the Sierra Club, researchers found the DEIS’s traffic analyses were misleading. The models were applied inconsistently across geographies, allowing UDOT to present the no-build alternative as extremely untenable.

Musicians weighed in on the project too. Country music singer and songwriter Brenn Hill wrote the song “Legacy Highway” expressing his frustrations about the plan. The title of this blog post comes from the lyrics of that song. Listen to it here.

After one year of comments and federal reviews, UDOT and the Federal Highway Administration, the lead federal agency of the project, released the Legacy Parkway Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) in July 2000. Utah DOT’s new preferred plans would include a multi-use trail, cost only $369 million, fill only 46 acres of wetlands, and impact the second least amount of developable land compared to alternative highway plans.

While UDOT’s Final Environmental Impact Study portrayed Legacy Parkway as a principled compromise that could both meet the automotive travel demands of 2020 and preserve wetlands, it still ignored much of the substantive criticism levied against the models in the earlier Draft Environmental Impact Statement. As UDOT forged ahead, awarding construction contracts as early as December 2000 (before they’d received final permits), Utahns for Better Transportation, the Sierra Club, and Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson took the only recourse left to them: they filed a lawsuit.

Lawsuit

Construction on the Legacy Parkway began in January 2001, just after the Federal Highway Administration approved the Legacy Parkway FEIS. With no other recourse, Utahns for Better Transportation, the Sierra Club, and Salt Lake City Mayor Rocky Anderson sued the Utah Department of Transportation and participating federal agencies to stop the construction of Legacy Parkway. The plaintiffs brought their issues against the DEIS and FEIS to the Utah District Court.

Elected leaders make a difference

It should not be too surprising that Anderson, a mayor known for his ardent advocacy for sustainable municipal policies, joined the suit. Since the start of his term in 1999, Mayor Anderson had seen the outsized impact that Salt Lake City’s TRAX light rail system had on the city and presided over network improvements that improved daily ridership vastly beyond initial projections. Local support for transportation alternatives grew to be so strong that voters in the city passed tax increases—on themselves—to support the development of new mass transit infrastructure. Building off of public support for these new systems, Anderson stated that “with the commitment by the community to mass transit comes a commitment by our Administration to transit-oriented development.”

While the first case against Legacy Parkway was dismissed in the Utah District Court, the coalition of advocates appealed the decision in the 10th Circuit Court of Appeals. In November 2001, the court issued an injunction and forced the Utah Department of Transportation to cease construction. After nearly a year of review, the Court found that the federal agencies’ Environmental Impact Statements were inadequate “to the point of being arbitrary and capricious.”

The court forced the agencies to develop a Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement that addressed failures to adequately consider harm to wildlife, alternate highway routes, narrower median design (the design included in the 2000 FEIS would have allowed for future expansion to six lanes), and mass transit. UDOT and the FHWA developed a new impact statement to account for the original deficiencies from 2002 to 2004, but by then, the project could not afford any more lawsuits.

Compromise

Advocates might have won the battle, but they lost the war. They negotiated a compromise with UDOT while the Final Environmental Impact Statement was being drafted, winning concessions like $2.5 million for rapid transit studies, an additional $12 million for land preservation, and unique provisions banning semi-trucks and lowering Legacy Parkway’s speed limit (an ineffective solution to dangerous roadway speeds, as we wrote in Dangerous by Design).

Construction resumed in March 2006, Legacy Parkway was completed in 2008, and just 12 years later, the provisions expired, allowing the speed limit to increase and semi-trucks to drive on the parkway. By making a few temporary compromises, UDOT successfully greenwashed the first segment of the 120-mile-long Legacy Highway network that now transports 20,000-30,000 vehicles a day.

When Legacy Parkway opened, it was celebrated by motorists for its scenic routes and tranquil views of sunflower blooms along its meandering path. Ironically, drivers enjoying the views now contribute to emissions in a region with some of the worst air quality in the nation. To build the parkway, over 4 million tons of material had to be used to fill in the wetlands below the road and the concrete and steel used in construction could have produced as much as 40,000 tons of CO2. It cost 685 million dollars.

Better build another highway

Though planners miscalculated how dramatic population growth would be in the past, the counties surrounding the Great Salt Lake will no doubt continue to see major growth. But rather than taking congestion as a sign to innovate new solutions, like a hammer looking for a nail, UDOT uses the all too familiar tool of highway expansion to “solve” congestion. Lane additions and highway expansion every 10 years can’t solve traffic and certainly will not improve ecological outcomes, but it can cost the public their health and hundreds of millions of dollars for a handful of miles.

Now UDOT has new plans for a northern expansion of Legacy Parkway, meant to address still further population growth projections. UDOT and FHWA have familiar words for the project, called the West Davis Corridor:

By 2040, the number of households in this region will increase by 65 percent. This population growth requires a solution that addresses upcoming transportation needs while minimizing impact to the community and environment. After a thorough analysis of fifty-one alternatives, a preferred alternative (West Davis Highway) has been identified. By 2040, this one project would reduce all congestion west of I-15 by one-third.

This new highway will include a land preserve and a recreational trail as part of its environmental impact mitigation strategy. While the interchange to I-15 is being constructed, traffic is being routed over the Legacy Parkway. The budget for the West Davis Corridor project is $800 million.

State DOTs would have us believe that highways are the solution to population growth, but history has proven otherwise. Costly highway projects always seem to require a new costly highway project, and the endless cycle only makes conditions worse for the environment and people who live around and drive on these roadways. While advocates did succeed in changing the course and character of Legacy Parkway, this compromise failed to make lasting change. To do that, we need more than compromise. We need a fundamental change in our priorities.

The post Better build another highway: The Legacy Parkway story appeared first on Transportation For America.